Trish Parker settled into the back seat of a rented Mercedes for a final trip out of Liestal, Switzerland.

Jud Parker, one of the 90-year-old woman’s three adult sons, drove. Another son, Reed Parker, sat next to him. Their mom loved the idea of being chauffeured for this special occasion.

Liestal is in the Basel-Landschaft canton, in the northern part of the country. It’s an industrial town that has retained its historic charm. Its roots plunge even deeper than its founding eight centuries ago. Most of the 14,000 or so people who live there speak German.

It was Thanksgiving Day 2024. And the family was far from the Ohio home where Patricia Ann “Trish” Regenhardt, had raised the boys, outlived two husbands and painted daily in a home studio filled with light.

They’d spent the last few nights at a four-star hotel with an in-house restaurant called Mad Angel. They’d enjoyed visits to nearby Swiss shops. They took in the sights. Sampled the food. Almost like a mini-vacation. But now they were headed farther north, through unfamiliar territory to the city of Basel. On their way to an equally unfamiliar − yet welcome −destination. The kind of place Trish thought about many times before.

“It was just so surreal,” Jud Parker, 64, the middle child, recalled.

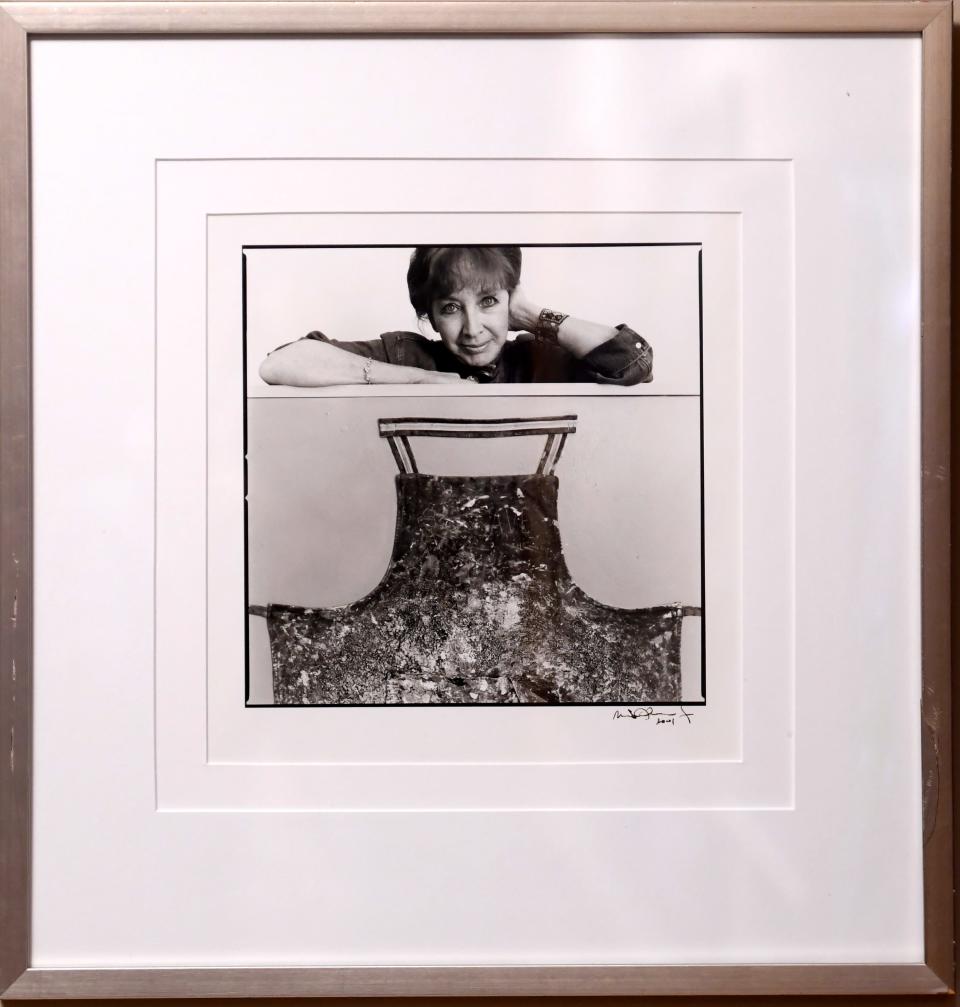

A photo of Plain Township artist Trish Parker hangs on a wall inside her son Jud Parker’s Jackson Township home. The 90-year-old Parker had long planned a physician-assisted death.

He remembers so many details, while others remain a blur, from those few days the three shared. Brother, Reed, is three years older; he lives in California. The youngest sibling, Curtiss, lives in South Padre Island, Texas. All agreed it was best he not join this trip, and he was fine with that.

“So, we’re driving through the countryside … mountains,” Jud recalled.

They got closer. He stared at directions on his cellphone. He recalled only bits and pieces of what they talked about during the 25-minute drive. He was so focused on not getting lost.

Finally, they arrived at the correct address, they believed. However, there were no signs posted to assure them it was the right place. Rain pelted the unassuming shop and office complex. A knock on one door led to another. They’d found it, the Pegasos Swiss Association.

It’s where Trish, an accomplished Northeast Ohio artist with three college degrees, planned to leave this world.

“She was probably the healthiest 90-year-old you’d ever meet,” Jud said.

No matter.

This was going to happen.

Trish had long ago decided this, for so many reasons.

Trish Parker is flanked by her sons, Reed Parker, left, and Justin Parker, in a photo from their Thanksgiving week trip to Switzerland.

Mom, artist, professor and a nod to Kevorkian

In a photo from the trip, Trish is flanked by Reed and Jud. They tower over their petite mom, a woman with neatly kept dark hair and radiant blue eyes.

“She was born an artist; it’s who she was,” said Jud. “A wonderful mom and outstanding artist,” Reed said.

Trish once was a child prodigy. Born Patricia Zinsmeister in 1934, she and a sister lived in Cleveland. At age 12, Trish received a gifted children’s program scholarship to the Cleveland Institute of Art. She’d go on to earn a four-year academic scholarship to Ohio University. She continued her art studies, though she didn’t graduate from the school.

In the 1950s, she married Esidore Justin Parker, and together, they raised the three boys. During their formative years, Trish was a stay-at home mom. Her artwork in those days was mostly relegated to sketching the children, or her husband. She also landed gigs as an American Greetings card designer and as a fashion illustrator for Polsky’s department store in Akron, Ohio.

“She was completely devoted to us children,” Jud said.

When the boys grew older, Trish returned to school.

She earned a bachelor’s degree from Kent State University in 1973 and a master’s two years later. She was hired as an adjunct professor at the University of Akron School of Art. In 1981, she earned a Master of Fine Arts, the highest offered in that particular field.

Some of Trish Parker’s life is captured in photos, which were displayed during a wake held at her home in late January.

Through it all, she painted and created for hours upon hours inside a warehouse in a building the university had rented for years. It was a studio haven for artists.

“I remember the giant ceilings … the second floor,” Jud said. “She’d go out on the fire escape to look around, and to get inspiration or whatever; you could see the railroad tracks.”

Painting became her life for the next half-century. On canvas and on paper, large and small. She preferred house paint, the same as revered artists Jackson Pollock and Pablo Picasso.

On her website, Trish’s work is described as narrative abstract expressionism: “Her painting methodology is based on a well honed sense of intuition acted upon with random gestures, which eventually suggest the content of the paintings and prints,” a statement noted. “The subject matter (iconic shapes, symbols and color tonalities) comes together in the ‘soup’ of pigment, collage and ideas which evolve with the flow of physical activity.”

The style was a conscious evolution from rigid realism.

In 2016, she wrote this about herself:

“My work has always had one salient component, that being an autobiographical one. I feel strongly that my life experiences have shaped and influenced my art. Many years ago during my time at Kent State University, I began to draw with my untrained left hand.

“What prompted this departure was a boredom with rendering objects realistically and a subconscious need to find a means of expression outside of formal artistic constraints. … My left hand gave me the tool to accomplish this goal.”

She painted under the name Patricia Zinsmeister Parker, or “PZP” for short. She traveled to France, Ireland, Spain, England, Italy and Mexico, but never Switzerland.

“The act of drawing is intrinsic to all visual art disciplines, and to express oneself through the basic mediums of paper and pencil or paint and canvas is to penetrate an interior, subconscious existence — one that is uncharted, yet rich in creative discovery.” – Trish Zinsmeister Parker

Her pieces, she explained, were diverse.

Sometimes, she just wanted to paint flowers, or rework vintage paintings. Other times she experimented with new materials in an abstract format. Always, she said she was guided by a premise “to stay true to my convictions as they relate to the integrity of purpose and motive.”

In 1976, she submitted two paintings — “Cold Pop” and “Mother Parker,” — to the Cleveland Museum of Art’s May Show. She continued to regularly enter pieces through 1990. In that span, she won nine juror awards. In 1982, she was awarded a best of show.

During the 1990s, her paintings were featured in places like the Bonfoey Gallery in Cleveland and Cleveland Center for Contemporary Art. She was awarded a research grant from the University of Akron and she was recognized by the Ohio Senate for her contributions to art. In the midst of success, Trish, like much of the nation, couldn’t help but hear, see and read news headlines about a physician named Dr. Jack Kevorkian.

A vocal proponent for rights of the terminally ill to choose how they die, Kevorkian helped as many as 130 people kill themselves. The cause landed him in prison. He died in 2011. To this day, he’s simultaneously praised as an icon and despised as a villain, depending on your beliefs.

Dr. Jack Kevorkian shown in this 1994 file photo. While he was tried multiple times in the 1990s, he was either acquitted or had charges dismissed due to Michigan’s lack of clear laws against assisted suicide. However in 1999, he was convicted of second-degree murder after directly administering a lethal injection to Thomas Youk, a man with ALS (Lou Gehrig’s disease). He was sentenced to 10–25 years in prison but was released on parole in 2007 due to declining health. He died in 2011.

“She was fascinated by Kevorkian; he was a hero to her,” Jud said.

Death is part of life, she’d say. They are forever intertwined.

“I’m going to do that, boys,” she told her sons during the Kevorkian years.

Sure mom, OK.

It didn’t quite register coming from the mouth of your 50-something mom, who’s quite happy and healthy. But Trish would continue to mention it, off and on, in the years ahead.

Her beliefs are what had led her to Switzerland. She and Jud flew from Cleveland to New York. From there, came a long flight to Zurich. Reed flew separately, from his home.

A desire to live and leave on her own terms

“She’d started to talk about it even more after our father died,” Jud recalled.

“It,” of course, being a planned, assisted death.

Trish’s first husband, Esidore Justin, died in 2001. He’d battled multiple myeloma, a blood cancer. He survived multiple strokes. It was a slow, difficult end to watch. That, Trish had said, would not happen to her.

She painted prolifically during the following two decades. The wooden floor of the home studio her husband built, still bears scars of her work — a rainbow of splotches, puddles and dribbles of misplaced paint. Trish’s pieces appeared all over from Ohio to New York.

A 1960s-era photo of Trish Parker and her husband, Esidore Justin Parker. He died in 2001 and she remarried.

Her second marriage was to Robert Regenhardt, a widower and an engineer by trade. He designed shelves, stretchers and contraptions to store and display Trish’s paintings.

Throughout their marriage, Trish continued to talk about dying on her own terms, the way she wanted, and when she wanted.

Her plan, Jud said, was probably only reinforced after his mom endured the death of Regenhardt on April 25, 2023. Much like the passing of her first husband, the end was lingering.

Trish Parker, who lived in Plain Township, was a prolific, and highly decorated, artist. Many of her works remain for sale today.

By then, Trish was 88 years old.

Her research into a planned death increased. She’d surf the web, reading about her options. Although 10 states (Ohio is not among them) and Washington, D.C., allow medically assisted dying, most require residency status and a verified terminal illness diagnosis.

Trish, though, didn’t want to leave Ohio and she was not dying. She was relatively healthy.

Those obstacles likely led her to Pegasos Swiss Association, the Swiss voluntary assisted death business. Its staff speaks English as well as German and much of the paperwork can be done online.

“I know she contacted them about six months after (the death of her second husband),” Jud recalled. “They told her she had to wait … so she did that. A year later, she asked again.”

They accepted her; she made arrangements.

Pegasos officials said they would not provide an interview about Trish’s visit there and could answer only general questions.

“Privacy and confidentiality are at the center of our commitment,” they wrote in an email. “This is why we cannot share, confirm, nor deny the identities of those wanting to die with Pegasos in public.”

Its website and a few news stories help to explain its business of voluntary assisted dying, which costs $11,000 in U.S. dollars.

The Pegasos story began in 2018. Its core team was involved in the “landmark death” of 104-year-old Australian ecologist David Goodall. He was not dying. But his quality of life was failing. He wanted to die.

According to the Pegasos website, Goodall’s plight demonstrated that “A person’s desire for a dignified and peaceful assisted death is not solely dependent on terminal illness,” and that “Swiss law on assisted suicide is well placed to serve the needs of people who may not fit the traditional criteria used in other places in the world where assisted suicide is legal.”

Simply put, assisted dying is lawful in Switzerland if the person is mentally competent to make decisions, has unselfish motives, and controls the device which administers a death drug.

“She’s the one who set up the appointment,” Jud said.

Trish told her family.

“She said, ‘I am going to do this, and I want you to support me 1,000%, or I’m going to go without you,'” Jud recalled.

A friend told Jud his mom was being selfish. Nothing, he said he soon realized, could be further from the truth. She was simply candid and honest with the people she loved most. Was her decision cowardly, his mom asked? Absolutely not, he said. He told her she had guts.

He and the rest of the Parker family told her they supported her decision − after all it was her decision.

Trish Parker had long explored the idea of physician-assisted death.

“She made it clear this (option) wasn’t for everyone,” Jud said, adding she would have wanted him to share her story because, “she also wanted people to know this option does exist.”

Besides her three sons, Trish had five grandchildren. In the weeks before the trip to Switzerland, she took some to lunch. There was no talk of death. No mention of what was to happen. No sadness. Just a grandmother and them spending time together. And when the time came, there was to be no tear-filled funeral. Absolutely not, she insisted. She wanted an Irish wake.

Happy, fun and celebratory.

After all, death is merely part of life.

Jud was on board, but still …

“I said ‘listen, if we get there and you don’t want to pull the trigger, we can just get on a plane and come back home,” he recalled telling her.

Trish scolded Jud with a profanity-infused tongue-lashing.

This was going to happen, she told him.

End of life choices in Ohio and across the US

Decades ago, the idea of being prescribed medication to end your own life, was typically referred to as assisted suicide. Many called the notion ghoulish. Kevorkian was called “Dr. Death” in the media.

Pegasos refers to the practice as voluntary assisted dying. In the U.S., it’s commonly known as physician-assisted suicide, or more specifically these days, medical aid in dying.

“It’s about living your life with an understanding that death is a part of it,” said Lisa Vigil Schattinger, executive director of the nonprofit Ohio End of Life Options.

The group’s mission is to raise awareness about medical aid in dying and provide “fact-based education” while working with a partner political fund to convince state lawmakers to pass an assisted dying law.

Lisa Vigil Schattinger, executive director of Ohio End of Life Options, and board chair of the Death with Dignity Center.

Oregon was the first state to enact a so-called “Death with Dignity Law.” Voters approved it in 1994; it took effect in 1997. The law withstood an onslaught of legal challenges, all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court. Since 2008, voters, lawmakers or state Supreme Court decisions have made assisted dying legal in Washington, D.C., and in the states of Washington, Vermont, Montana, California, Colorado, Hawaii, New Jersey, Maine and New Mexico.

Rules in those places are similar, Schattinger said. Patients must, for example, have less than six months to live. Medical providers − who can’t, for instance, morally reconcile the Hippocratic principle of “do no harm” − are not required to participate in assisted dying.

When told of Trish’s story, Schattinger said she respected it.

“As an adult, I have been making decisions all my life, but at the end of life, I can’t?” Schattinger asked.

However, she added Ohio End of Life Options is focused on adults who have less than six months to live, are mentally competent and can ingest assisted dying medications. Ideally, she said, Ohio would adopt a legal template used in other so-called “Death with Dignity” states.

“We want to work within that framework,” she explained.

Schattinger also is president of the board of directors for the national nonprofit Death with Dignity Center in Portland Oregon. That group considers Oregon’s assisted death law as a model to follow.

“Our mission focuses on improving how people with terminal illness die,” the center website states, in part. “We know some people die in horrible ways as their terminal illness overtakes them. In our current healthcare landscape, that is undeniable. And, it’s unacceptable.”

Reasons for suicides are complex. Many can be related to a mental illness. But there are other instances, which even local experts acknowledge, could possibly be outliers of sorts:

Last year, in Stark County, Ohio, the coroner’s office ruled at least 71 deaths suicides. The Canton Repository, part of the USA TODAY Network, found that in as many as 10 of those cases the suicide was completed by someone who was terminally ill or had been living with chronic physical pain.

An abstract self-portrait of Trish Parker is on display at her son Jud’s house.

They included a 75-year-old who’d complained about poor quality of life, and whose lung cancer had spread to his lymph nodes and a 59-year-old man whose blood test results prompted an urgent summons from an oncologist. Another 59-year-old man had lived with unrelenting pain for years and was largely immobile, needing both hips and knees replaced.

A 63-year-old Canton man battling a series of health problems had just received test results, a family member said. He left a $2,000 check to pay for cremation and a note which stated “physically ill, mentally spent, done, love to mother, uncle, brothers, family … “

The Stark Coroner’s Office and Stark County Mental Health & Addiction Recovery recently joined forces, in an effort to better understand and analyze suicides, which could aid in future intervention. Outside of suicide, the only way for a terminally ill person in Ohio to hasten their own death is to refuse life-prolonging treatments or to stop eating and drinking. Neither, Schattinger said, are recommended without professional guidance and support, such as hospice care.

Trish Parker typically painted under the name Patricia Zinsmeister Parker throughout her career.

Trish and her sons had left the U.S. for Switzerland four days before Thanksgiving. Again, “surreal” was the word Jud often used to describe much of the trip. On one hand, the three had so much fun. Still, he could almost envision “the grim reaper” reaching from behind.

When a Pegasos physician visited, Jud said the doctor told his mom that many Pegasos patients were in a wheelchair or on oxygen. A healthy Trish used neither. Maybe she wanted to wait; give it more time?

“We are doing this tomorrow,” Trish insisted.

Trish ‘nailed them all,’ as a wife, mother and artist

In 2018, then-state Sen. Joe Schiavoni, co-sponsored an assisted dying bill in Ohio but it never made it out of committee. Now a part-time judge in Mahoning County, Schiavoni said he knew the bill wouldn’t become law.

But that wasn’t the point.

Jud Parker’s Labrador retriever strolls down a hallway at his Jackson Township home, which features some of Trish Parker’s artwork.

“It was just trying to get the discussion to move forward … to have the conversation continue,” he said.

But even if legal, is assisted death moral?

Death with Dignity foes, much like anti-abortion advocates, would loudly shout ‘no!’ Both similarly cite arguments about sanctity of life, ethics and a spiral toward possible euthanasia.

Those same issues often are rooted in religious views −Trish was raised Catholic, but no longer practiced.

All four of the world’s major religions − Christianity, Islam, Hinduism and Buddhism −oppose physician-assisted death and euthanasia, according to “Perspectives of Major World Religions regarding Euthanasia and Assisted Suicide: A Comparative Analysis,” an article published in the December 2022 issue of the Journal of Religion and Health.

“This contrasts with a secular and atheistic worldview … ” the authors wrote.

One reason for the divergence, the authors explained, is because followers of all four religions believe in a higher being.

“This inevitably leads practitioners of these religions to seek to understand morality not from within but instead in accordance with this external arbiter,” the article stated.

Although now constrained by judicial canons, Schiavoni said as a state senator he would have argued everyone is an individual; that providing a right to assisted death does not force it upon anyone.

“That there should be a path in place,” he said.

“Yes, we do need a change,” Schattinger said.

After the physician visited Trish the day before Thanksgiving, a nurse came by hours later. He explained how she would get an IV line. And that she was the one who’d ultimately push the button to administer a lethal dose of the barbiturate Nembutal (pentobarbital sodium).

“He said, ‘You will go to sleep, but you won’t wake up,'” Jud recalled.

A few tears snuck out; he couldn’t help it.

On Thanksgiving, when Trish and her sons had arrived at Pegasos, they were invited inside. She and her sons, and five Pegasos staff members sat in a large room. They indulged in what he described as cocktail hour-style conversation for the better part of 90 minutes.

“Art, politics, travel,” Jud recalled.

But nothing about death − until finally, Trish interjected.

“OK, it’s time to do this,” she announced.

She went to the bed near a window on one side of the room.

Jud and Reed followed.

An urn holding Trish Parker’s ashes, surrounded by photos of her.

“Boys, I think you should go in the other room,” she said.

Jud said his knees buckled as he and his brother walked out.

Twenty minutes later, it was over.

Trish was dead.

Jud and his brother returned to the room to say goodbye to their mom. Reed, he said, thanked her. Jud said he was frozen. He couldn’t find the right words. He still regrets that.

He hopes she knows, though.

“She was the best mother, wife and artist; she nailed them all,” Jud said.

Contact Tim Botos at tim.botos@cantonrep.com. On X: @tbotosREP

This article originally appeared on The Repository: Assisted suicide chosen by artist inspired by Kevorkian assisted death

#Prolific #Ohio #artist #wanted #leave #life #terms #traveled #Switzerland

Leave a Reply