BBC

BBCOn 26 January, thousands of displaced Lebanese, who had been living across the country, tried to return to their homes in southern Lebanon.

They travelled in convoys, played revolutionary songs and waved, proudly, the yellow Hezbollah flag. Many found out that, aer more than a year of war, there were no homes to return to. They mourned what had been lost and, in the rubble of destroyed buildings, put up posters remembering the group’s late leader, Hassan Nasrallah.

The date marked the end of a deadline for the withdrawal of Israeli troops, part of a ceasefire brokered by the US and France, that required Hezbollah to remove its weapons and fighters from the south. The deal would also see the deployment of thousands of Lebanese soldiers in the area. But Israel said Lebanon had not fully implemented the deal and, as a result, not all invading forces pulled out. Lebanon also accused Israel of procrastination.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesUnsurprisingly, there was violence. In some areas, Israeli soldiers opened fire and 24 people, including a Lebanese soldier, were killed. Still, for Hezbollah, which has been the dominant force in southern Lebanon for decades, the violence was an opportunity to project strength, after being battered in the conflict with Israel. But can the group survive a wave of changes in Lebanon, and the re-shaping of power in the Middle East?

Ability to paralyse

Over the years, Hezbollah, the Shia Muslim militia, political and social movement, cemented its position as Lebanon’s most powerful group. Backed by Iran, it built a military force more formidable than the Lebanese army. The use of violence was always an option. A strong parliamentary bloc meant that no major decision was possible without its consent while Lebanon’s fractured political system gave it representation in the government. In short, Hezbollah had the ability to paralyse the state – and many times did so.

The latest conflict started in October 2023, when Hezbollah opened a second front against Israel as Israel launched a war in Gaza in response to the Hamas attacks. The hostilities escalated dramatically last September, as Israel had penetrated the group in ways then unimaginable. First, pagers carried by its members exploded. Then their walkie-talkies. An unrelenting air campaign and subsequent invasion of the south killed more than 4,000 people including many civilians, left areas with a significant presence of Shia Muslims – which form the bulk of Hezbollah’s support – in ruins, and severely damaged the group’s arsenal.

Many of its leaders were assassinated, most notably Nasrallah, who had been Hezbollah’s face for more than three decades. His successor, former number two Naim Qassem, who is not as charismatic or influential, has admitted they suffered painful losses. The ceasefire deal that came into force in November was essentially a surrender by the group, which is considered a terrorist organisation by the US, the UK and others.

Getty Images

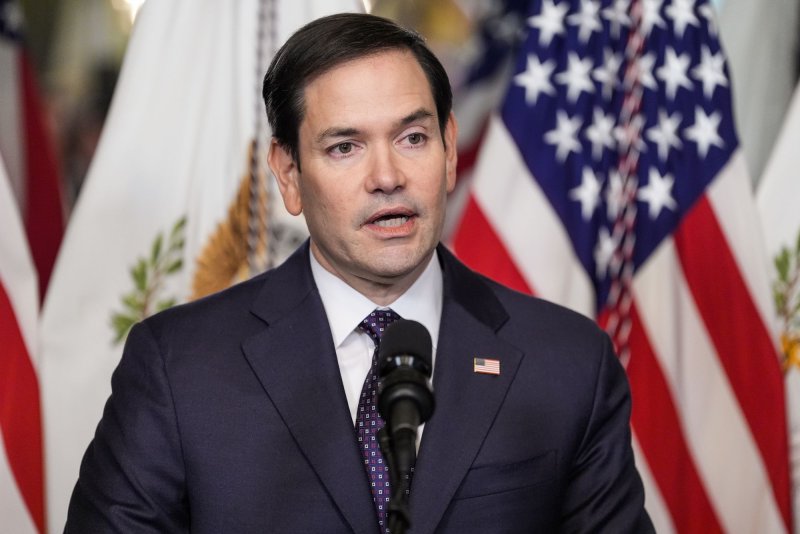

Getty ImagesIn this new reality, last month, Lebanon’s parliament finally elected a new president – former army chief Joseph Aoun, who was favoured by the Americans – after more than two years of impasse that critics attributed to Hezbollah. Weakened, the group could not block the process as it had done in the past.

In another sign of its diminished position, Aoun then named as prime minister Nawaf Salam, who was serving as president of the International Court of Justice, and someone not aligned with the group.

Hezbollah, for now, seems to be focused on another priority: its base. The group has told its followers that the loss in the war is a victory, but many know the truth is different. Their communities are destroyed, and the damage to buildings is estimated to be over $3bn (£2.4bn), according to the World Bank.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIn a country with a collapsed economy, no one knows who will help – if anyone, as international assistance has been conditioned on the government taking measures that would curb Hezbollah’s power. The group has paid compensation to some families, as it did after the 2006 war, but there are already indications of discontent.

“If people are still living in tents in six months’ time, or on the rubble of their homes, they may start to blame Hezbollah rather than the government or Israel. This is why they’re investing so much effort now to try to pre-empt that,” says Nicholas Blanford, a Beirut-based non-resident senior fellow with the Atlantic Council’s Middle East programmes and the author of Warriors of God: Inside Hezbollah’s Thirty-Year Struggle Against Israel. “In the current context, you can push back a little bit against Hezbollah.”

An implicit threat

But any action against Hezbollah comes with risks.

On 26 January, hours after people tried to return to the south, young men on motorbikes drove through non-Shia areas of Beirut and other places at night, honking and carrying Hezbollah flags. Residents in some areas confronted them. In a country where sectarian divisions run deep and many still remember the days of the 1975-1990 civil war, the convoys were seen as an intimidation tactic.

Mr Blanford said Hezbollah had “the implicit threat of violence” because of its military arm. “If you push them too hard,” he said, “they will slap you back very hard”. A Western diplomatic official, who spoke on condition of anonymity in order to discuss private talks, told me: “We’ve been telling players here [the opposition] and in other countries: if you corner Hezbollah, it will probably backfire, and the risk of violence is a real possibility.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesStill, a new chapter has been opened in Lebanon, a country exhausted by pervasive corruption, government mismanagement and seemingly endless violence. It is a combination that has resulted in a dysfunctional state.

Addressing the Lebanese parliament in his inaugural speech, Aoun promised ambitious and long-delayed reforms with the knowledge that, without profound changes, Lebanon cannot be rescued. He vowed to rebuild public institutions, revive the economy, and, crucially, make the Lebanese army the sole carrier of weapons in the country. Aoun did not mention Hezbollah by name, but this is what he meant. The chamber enthusiastically applauded him; Hezbollah parliamentarians observed in silence.

A regional issue

But the decision about Hezbollah’s existence as a military power will probably be made far from Lebanon – in Iran. For decades, Tehran invested with weapons and money in a regional alliance it calls the Axis of Resistance, which constituted a ring of fire around Israel. Hezbollah was its main player. With thousands of well-trained, battle-hardened fighters and a vast arsenal that included long-range precision-guided missiles on Israel’s doorstep, the group acted as a deterrent against an Israeli attack on Iran’s nuclear facilities.

This deterrence, for now, is gone – and rebuilding it, if that is Iran’s wish, will not be easy.

The fall of the Assad regime in Syria in December – in part because of Hezbollah’s setbacks – has interrupted the land corridor Tehran used to arm and fund the group. Israel, which has gathered extensive intelligence about Hezbollah, says it will continue to carry out attacks on the group to prevent its attempts to rearm.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesMr Blanford told me that “only Iran can really answer fundamental questions” about Hezbollah. “There is a possibility where either Iran or they [Hezbollah] decide to try to think differently, to disarm or become only a political party and social movement,” he said. “[But] this [ultimately] is Iran’s decision, out of the hands of Hezbollah.”

I asked a source familiar with Hezbollah’s internal affairs whether it was realistic to talk about the group’s disarmament. The issue, the source said, could be part of a “bigger, regional negotiation”, in what appeared to be a reference to indications by Iran that it is willing to reach an agreement with the West over its nuclear programme. “And there’s a difference between giving up weapons entirely or working under a framework with the state about their use, which is another possibility,” the source added.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesLebanon’s new leaders are under pressure to act quickly. Foreign allies see the reshaped balance of power in the Middle East as a chance to weaken Iran’s reach even further while the Lebanese are anxious for some stability and to have a sense that the rules apply to everyone. People here dislike when they are described as “resilient”, given their ability to carry on amid the chaos. “All we want is to live in a ‘normal country’,” I heard from a frustrated resident in a mainly Christian area of Beirut last year. It is also the case that after so much suffering, even Hezbollah’s supporters may be questioning what role the group should play.

Hezbollah is unlikely to return to what it was before the war. Disarming may not be as unthinkable as it once was.

BBC InDepth is the home on the website and app for the best analysis, with fresh perspectives that challenge assumptions and deep reporting on the biggest issues of the day. And we showcase thought-provoking content from across BBC Sounds and iPlayer too. You can send us your feedback on the InDepth section by clicking on the button below.

#Battered #defiant #Hezbollah #Lebanon

Leave a Reply