LC De Shay, Data Work By Elena Cox

PeopleImages.com – Yuri A // Shutterstock

While much of the recent conversation around caregiving in the United States has focused on the acute crisis of unaffordable child care and the challenges for parents, another issue is looming: caregiving for the country’s fast-growing, aging and ailing population.

The U.S. population aged 65 and older grew five times faster than the total population between 1920 and 2020, according to the 2020 Census. While older adults today are expected to live longer than generations past, they face a higher chance of living with chronic conditions such as diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, and disabilities, among others, according to data gathered from the Gateway to Global Aging Data and published in The Journals of Gerontology in 2024.

The National Alliance for Caregiving and AARP reported in 2020 that an estimated 48 million Americans were providing ongoing care for adults over 50. The Labor Department has indicated the demand for home health and personal care aides is projected to grow 21% over the next decade—significantly faster than the average for all occupations.

Considering how many home caregivers are already underpaid or unpaid in every state, urgent support in the health care system is needed. QMedic examined data compiled by Medicaid, KFF, and the Labor Department to see how spending on home and community-based services varies by state.

Long-term care for adults can require on-demand care, as well as knowledge of complex medical conditions such as dementia, Alzheimer’s, or other chronic and degenerative disease. Even so, most caregivers are informal and unpaid. Between 2021 and 2022, over 37 million people in the U.S. provided unpaid elder care, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Most elder care providers were women, and nearly half provided care at least a few times a week. Those who receive wages typically receive an income below the national median pay.

Established in April 2024, the Ensuring Access to Medicaid Services Final Rule aims to alleviate caregiver burdens by reducing pay inequity by requiring home care companies to pay 80% of Medicaid payments toward workers’ wages rather than to defray overhead costs or add to profit. However, the new rule has been contested by payers for financial implications and a “one-size-fits-all” solution in a country where Medicaid programs operate differently from state to state.

According to KFF, of the nearly 3 million direct care paid workers in 2022, nearly 9 in 10 were women, about 7 in 10 earned low wages, and more than 1 in 4 workers were Black. This overrepresentation of Black women in caregiving has been longstanding. It is rooted in the country’s fraught history of chattel slavery, where enslaved Black women were made to serve as caregivers to the families of their enslavers while being separated from their own families.

Even today, paid caregiving is still strongly associated with the view that it is women’s work, which generally implies low wages and, ironically, no access to benefits such as health care, sick days, or retirement. These women caregivers are also often Black, Latina, Asian American, and Pacific Islander. Though caregivers provide a critical service that underpins society, given the rising cost of living, they are finding themselves hemmed into unfavorable work environments that offer no relief for their own families.

While the median cost of in-home long-term care in 2023 hovered around $6,000 per month, according to Genworth Financial’s 2023 data, caregivers earned a mean hourly wage of $16.12. That equates to about $2,700 per month before taxes, assuming caregivers work eight hours per day on weekdays.

![]()

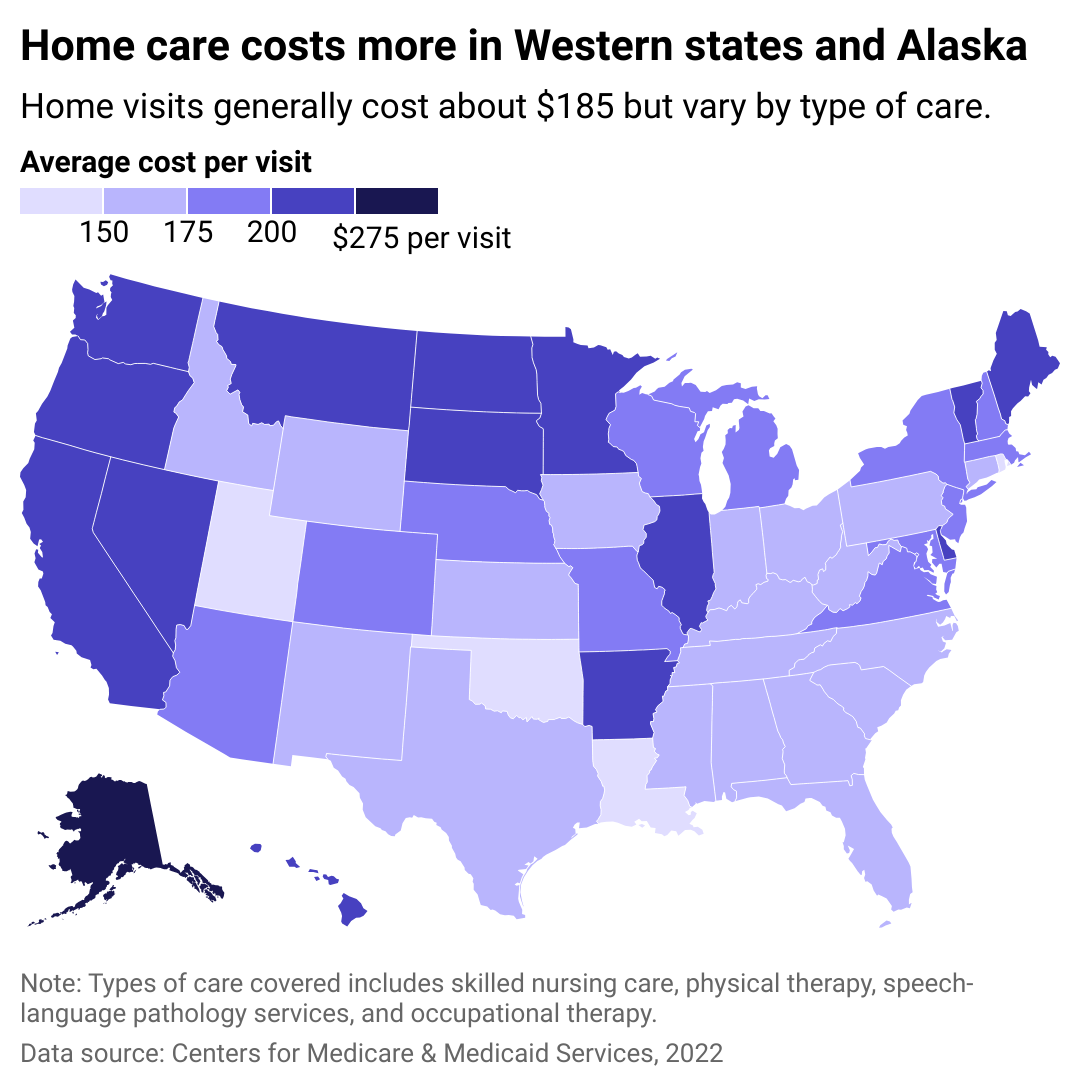

Home care visit costs vary by state

QMedic

Care for older adults at home can range from physical and speech therapy (considered home health care) to help with feeding, grooming, and walking, which is considered “home care” or personal care services. The former must be prescribed by a doctor and performed by a registered nurse or a licensed professional nurse with supervision. The latter can be done by nonlicensed caregivers and certified nursing assistants. These services allow older adults to stay in their homes longer, surrounded by their communities rather than in a nursing home or assisted living facility.

Still, care does not come without a cost: Most often, in-home care is paid using life insurance, long-term care insurance, or personal savings. Medicare can cover some of the cost, though it will not cover care for daily living activities such as bathing, feeding, and help using the toilet.

Medicare covers health care services for the homebound, which includes people who are advised to stay at home because of their condition. This includes assistance that is either part-time (up to eight hours a day and a maximum of 28 hours per week) or intermittent (less than eight hours per day and 35 hours at most each week).

Older adults may also qualify for Medicaid. Qualifications vary from state to state, and income in relation to federal poverty levels is usually considered. Medicaid also has a home—and community-based services waiver program that allows those who need care to hire and pay their family members as caregivers. According to KFF, about 2 million people in the U.S. receive some type of Medicaid HCBS through their states, but the costs vary widely.

According to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, the cost of care was highest in Alaska, with about $308.63 per visit. Nonprofit public policy organization Alaska Common Ground notes that health care costs are high in the state for many reasons, including for its small population, which lives in various remote areas and has limited access to medical service providers. Health care costs in Oregon have also increased dramatically, with residents spending nearly a quarter of their budget on health expenses, according to 2021 data from the Oregon Health Authority, a governmental agency.

Price is increasingly becoming a burden for adults. Though 1 in 5 adults say they receive support from family, friends, or paid nurses and aides, the same number also say they need more help. Unfortunately, according to KFF, 3 in 4 people cannot afford that extra pair of hands.

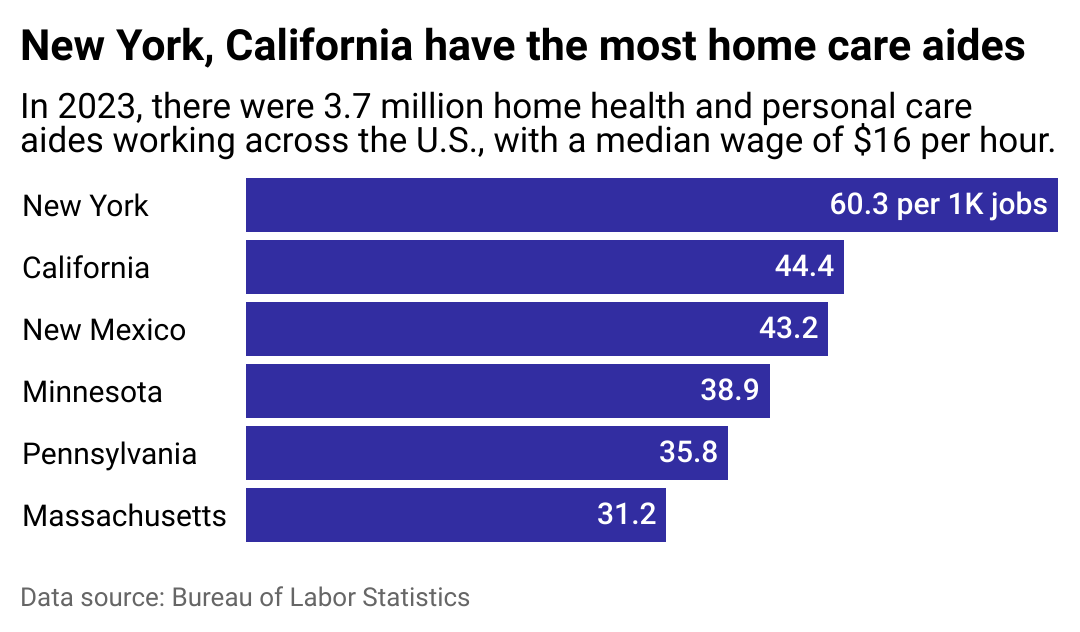

Home health care workers concentrated on the coasts

QMedic

The home health and personal care sector faces major challenges in recruitment and retention. “We are looking all the time for workers because we have over 10,000 hours a week of personal care we can’t find workers to cover,” Betsy Sawyer-Manter, CEO of SeniorsPlus, a home-based care provider in Maine, told NPR. Maine has about 28 home health workers per 1,000 jobs, according to the BLS, and also one of the largest percentages of people over 65 in the country, followed only by Florida, which presents one of the greatest shortages at 8.6 home health workers per 1,000.

With about 60 people employed per 1,000 jobs, New York has the largest population proportionally of home care aides. According to BLS data analyzed by Bill Hammond, senior fellow at Empire Center, New York’s health care workforce overall grew about 14%, an increase twice the average rate versus all occupations statewide. Most of that increase came from “healthcare support occupations,” which include home health aides.

In California, the second-largest population proportionally of home care aides at 45 people per 1,000 jobs, demand for these workers is projected to increase 29% by 2030, according to the Public Policy Institute of California. Knowing the challenges of pay and retention, the state approved an increase in the hourly minimum wage for its health care workers to $25, at which point, health care workers would no longer need to lean on programs like Medi-Cal and CalFresh to help bridge the gap between their wages and their daily living needs, according to a UC Berkeley Labor Center cost analysis. The legislation would increase wages for health care workers in the state by over $10,000 per year.

The Medicaid 80/20 rule—which requires that 80% of Medicaid payments go directly to workers’ wages—aims to alleviate the plight of home health care and personal care workers. Though energetically debated by the public before its approval, this regulation could signal a future in which long wait times due to worker shortages are decreased and caregivers—especially those who are Black, Latino, Asian American, or Pacific Islander—are given higher wages to continue providing care to a fast-aging population.

To increase equitable compensation, Medicaid 80/20 requires states to collect and report data in three years’ time on the percentage of Medicaid payments for homemakers, personal care assistance, home health aides, and habilitation services spent on compensation to direct care workers.

In four years, states must also report the percentage of Medicaid payments for the HCBS and establish advisory groups for direct care workers, beneficiaries, and other affected parties that meet at least every two years to provide feedback and consultation on payment rates.

Once implemented, this rule is expected to reduce premiums and out-of-pocket costs for around 860,000 eligible individuals, according to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, potentially decreasing the financial burden for many families.

As the older adult population rapidly increases nationwide, families will be hardest hit financially and emotionally to care for their loved ones and will hold on to any reforms in the health care system that help them alleviate the burden.

Story editing by Carren Jao and Shanna Kelly. Additional editing by Kelly Glass. Copy editing by Sofía Jarrín. Photo selection by Clarese Moller.

This story originally appeared on QMedic and was produced and

distributed in partnership with Stacker Studio.

#Caregivers #pay #Families #struggle #affordable #senior #care #payment #rules

Leave a Reply