The family of Chester Cunningham remembers him as a man who saw the good in everyone, and had a drive to help Indigenous offenders.

He died last month in Barrhead, Alta., at age 91.

Cunningham’s daughter Carola Cunningham says her dad “couldn’t stand bullies, couldn’t stand unfairness.” In 1970, he launched what would become Native Counselling Services of Alberta.

“He believed that all people were inherently good and that some people made bad choices,” said Carola Cunningham.

“But if you sat with them long enough and offered them choices, they could find their way back to being on track again.”

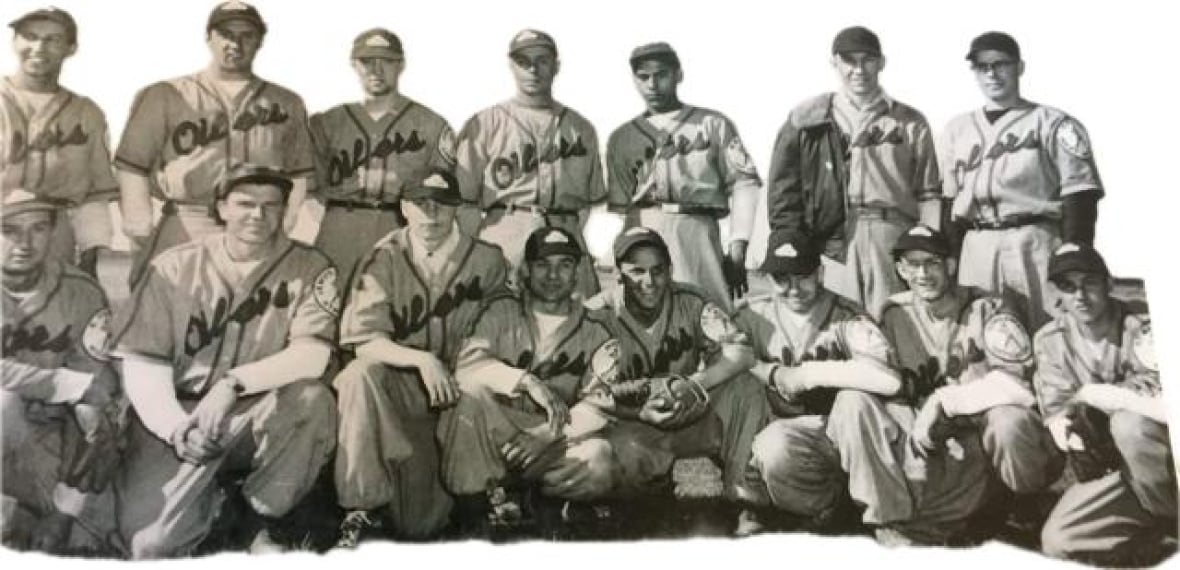

Cunningham, who was Métis from Slave Lake, Alta, left high school to play semi-professional baseball in 1952, joining a New York Giants farm team.

His son Dave Cunningham says an encounter with another player on the team only solidified his dad’s views on the extent of how racism could impact a person’s life.

When Cunningham arrived at training camp, most of the rooms were full.

“They didn’t really know where they were going to put dad, and they were saying, ‘Well there’s a room left … but you’ll have to bunk with Monte,'” said Dave.

That other player was Monte Irvin, one of the first Black players in the MLB. The organizers of the camp assumed Cunningham wouldn’t want to bunk with Irvin, because of his race.

“That’s where he kind of learned that there are all kinds of levels of racism and that it’s not a colourblind situation,” said Dave.

It was in those early years on the team that Cunningham learned about leadership, says Dave.

“He just really loved that game and the things that it taught him about managing and organizing, and keeping people together,” said Dave Cunningham.

Founded Native Courtworker Services

He was also a labourer and a miner, before becoming executive director at the Canadian Native Friendship Centre in Edmonton in the 1960s.

“He noticed all these people coming in, they’d come to the Friendship Centre, they’d have a coffee, they’d have lots of good conversations and they’d disappear,” said Carola.

Her dad wondered where they would go, realizing that many of them would end up incarcerated and thought it could be because of a misinterpretation of body language.

“Our people, when they’re listening intently, we use facial expressions, and we always say, ‘Yeah,’ and that’s a sign of respect,” said Carola.

But that reaction in the courtroom – she says – was often misinterpreted as a confession.

“Dad said, ‘Well, this is not right, we have to make some changes here.'”

Initially, Cunningham asked for support from the Friendship Centre to launch Native Courtworker Services, but at the time it didn’t fit their mandate.

“So dad made a decision with my mom and all the kids that he was going to lobby the government from the trunk of his car, basically,” said Carola.

“Mom was going to work full-time, and a lot of us kids got part-time jobs.”

In those early years, Allen Benson was hired as a court worker, and he remembers Cunningham’s strong sense of justice.

“He wanted fair and equal justice for all Indigenous people and equal access to justice,” said Benson.

“I remember in the early days when he said to me, ‘Never stop in a courtroom,'” he said.

“‘Sometimes the judges will get mad at you … but you push as hard as you can to make sure your clients get fair justice.'”

Large family

The organization would later be renamed Native Counselling Services of Alberta, and over the years programs a variety of programs have been launched, focusing on wellness, education, housing, and even programs to help residential school survivors.

Despite the long hours lobbying for NCSA, Dave Cunningham says his dad was “motivated and deeply committed to his own family,” which consisted of seven children, and his wife Elzaida Cunningham.

But he jokes that his family always seemed to grow, because his dad would become a father figure to many of his clients.

Cunningham received several local and national accolades including being appointed to the Order of Canada in 1983, receiving an honorary Doctor of Laws degree from the University of Alberta in 1989, and being made an honorary chief by the Piikani Nation in 1973.

#Chester #Cunningham #advocate #Indigenous #offenders #Alberta #couldnt #stand #unfairness

Leave a Reply