Centralized decisions can lead to unintended consequences and more fragile outcomes

-

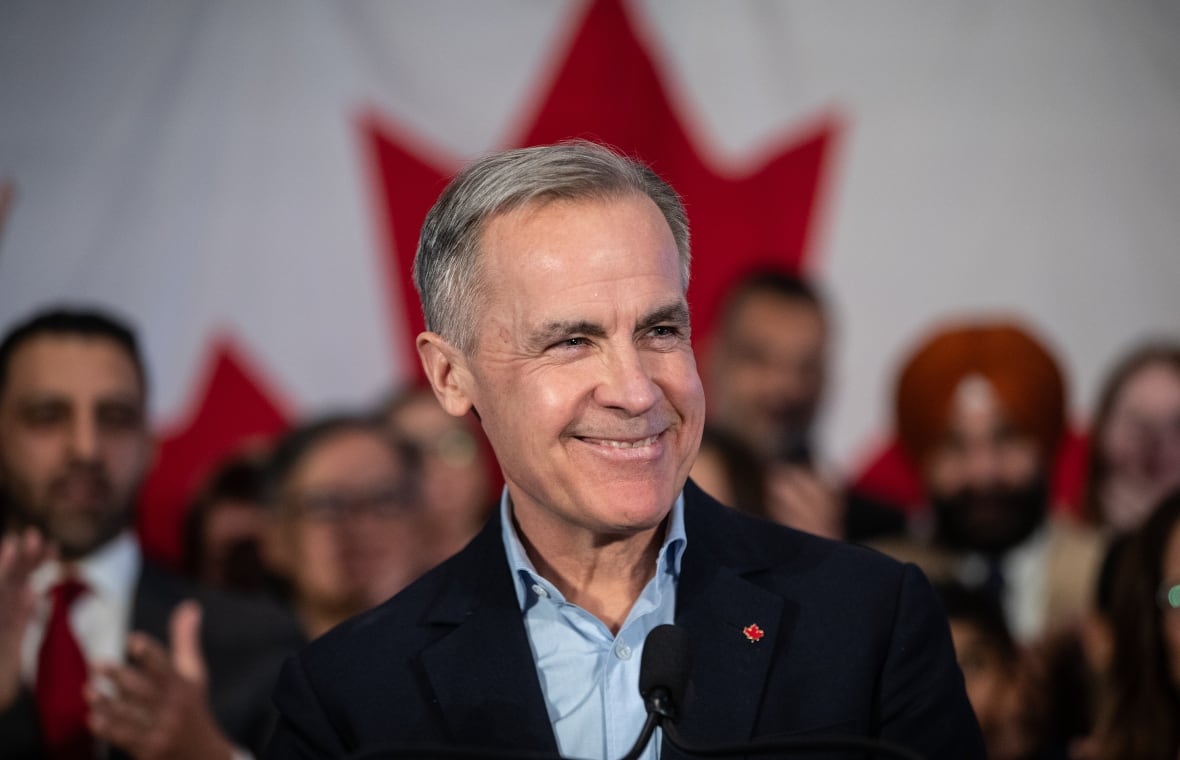

By Angela Huyue Zhang /

LONDON

Few predicted that TikTok users in the US would flock to the Chinese app Xiaohongshu in defiance of a US government ban. Yet in the space of just two days this week, Xiaohongshu became the most downloaded app in the US, gaining 700,000 users — most of them US TikTok refugees.

Since US data security was the rationale for the TikTok ban, US users’ migration to other Chinese apps only amplifies those concerns. Unlike TikTok — a platform that does not operate in China and is not subject to Chinese law — Xiaohongshu is a domestic Chinese app bound by strict Chinese regulations. Moreover, while TikTok says that it stores US user data exclusively within the US, with oversight by a US-led security team, Xiaohongshu stores its data entirely in China.

In recent years, China has introduced a series of data protection laws ostensibly aimed at safeguarding user information. However, these regulations primarily target businesses, imposing far fewer constraints on government access to personal data. Chinese authorities thus have wide discretion in requesting and accessing user data.

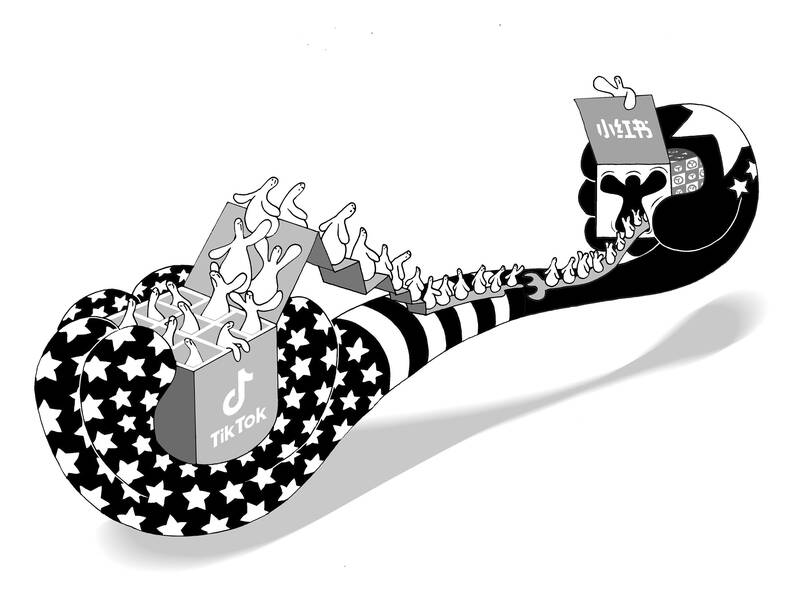

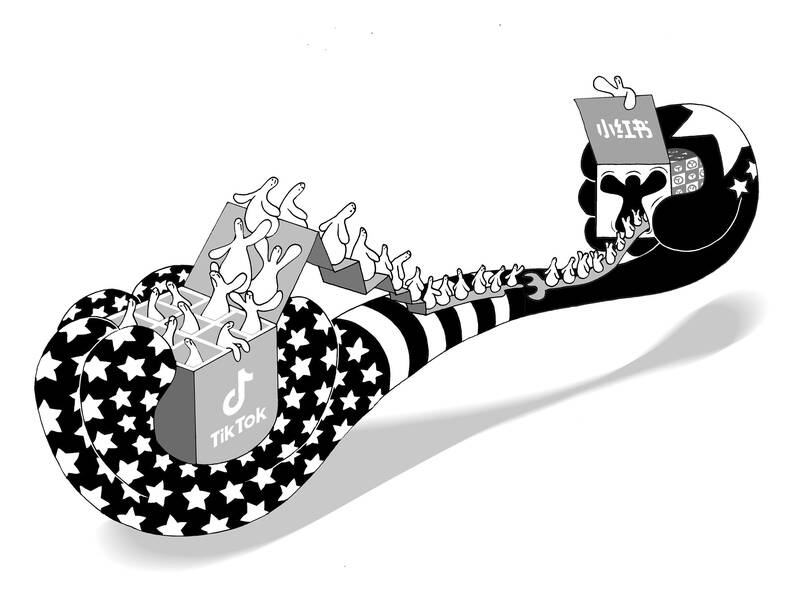

Illustration: Mountain People

Beyond the issue of data privacy, US authorities also worry that TikTok might be used to influence public opinion in the US. However, TikTok’s algorithms are closely monitored by Oracle, as part of a deal to address security concerns. In contrast, Xiaohongshu’s algorithms operate under the close scrutiny of the Chinese government, and the app is subject to China’s stringent content-moderation requirements, which could further shape the opinions of the TikTok refugees now flocking to the platform.

Given the rationale for the law banning TikTok, it is hard to imagine Xiaohongshu escaping similar scrutiny. Now that the US Supreme Court has upheld the TikTok law, the president has the authority to designate Xiaohongshu as a national-security threat, too. However, this process might quickly descend into a game of Whack-a-Mole. As US users migrate from one Chinese platform to another, regulators would find themselves locked in an endless cycle of banning Chinese apps.

As the list of banned apps grows, the US risks constructing its own “Great Firewall” — a mirror to the censorship strategy long employed by China. Even if Chinese apps are removed from US app stores, tech-savvy users could easily bypass such restrictions with virtual private networks, just as Chinese users do to access foreign platforms. That means the US government would soon confront the limits of its ability to ban Chinese apps.

Moreover, each new restriction risks fueling defiance, driving even more users toward Chinese-controlled platforms. Instead of mitigating national-security concerns, this strategy might inadvertently exacerbate them, introducing the kinds of vulnerabilities that the original ban was supposed to address.

The TikTok ban thus puts the US government in a near-untenable position, which might explain why US President Donald Trump is reportedly weighing options to spare TikTok (despite having initiated the ban during his first term).

Yet reversing the ban carries its own risks. As legislation passed by US Congress, it cannot be repealed by executive order. In theory, Trump could direct law enforcement agencies not to enforce the ban; but that would have far-reaching consequences, not least by calling into question the US’ commitment to the rule of law (again mirroring a charge the US has long leveled against China).

An alternative to banning TikTok is a forced divestiture of the app’s US operations, but that solution hinges on one critical factor: China’s approval. In 2020, China implemented restrictions on the export of technologies like recommendation algorithms — the core of TikTok’s operations — effectively giving the Chinese government veto power over any potential deal.

The TikTok dilemma thus now serves as a powerful bargaining chip for China’s leaders, granting them significant leverage in their dealings with Trump, who campaigned on a promise to impose higher import tariffs on Chinese goods. Not surprisingly, he turned to Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) for help just hours before the Supreme Court was set to weigh in on the ban.

At the same time, the TikTok saga has handed China yet another strategic gift. Friendly interaction between TikTok refugees and Chinese netizens on Xiaohongshu has created an unprecedented opportunity for cultural exchange, something China’s rulers have long aspired to, but struggled to achieve.

For over two decades, the Chinese government has aggressively tried to promote its culture and expand its influence in the US. While it has purchased ads in Times Square and established Confucius Institutes on US university campuses, these efforts have largely failed to gain traction. Remarkably, what Xiaohongshu has achieved in just a few days seems to have eclipsed the cumulative impact of all these prior initiatives.

As I explored in my recent book, High Wire, centralized decisionmaking frequently results in fragile, rather than resilient, regulatory outcomes. The TikTok saga offers a stark reminder that an overconcentration of presidential power in shaping US foreign policy — particularly toward China — could lead to similar outcomes. With Trump expected to consolidate executive power, surround himself with loyalists and operate with fewer institutional constraints during his second term, this trend seems likely to intensify, generating vast, unintended consequences.

Angela Huyue Zhang, professor of law at the University of Southern California, is the author of High Wire: How China Regulates Big Tech and Governs Its Economy and Chinese Antitrust Exceptionalism: How the Rise of China Challenges Global Regulation.

Copyright: Project Syndicate

#TikTok #boomerang #Taipei #Times

Leave a Reply